We Are America

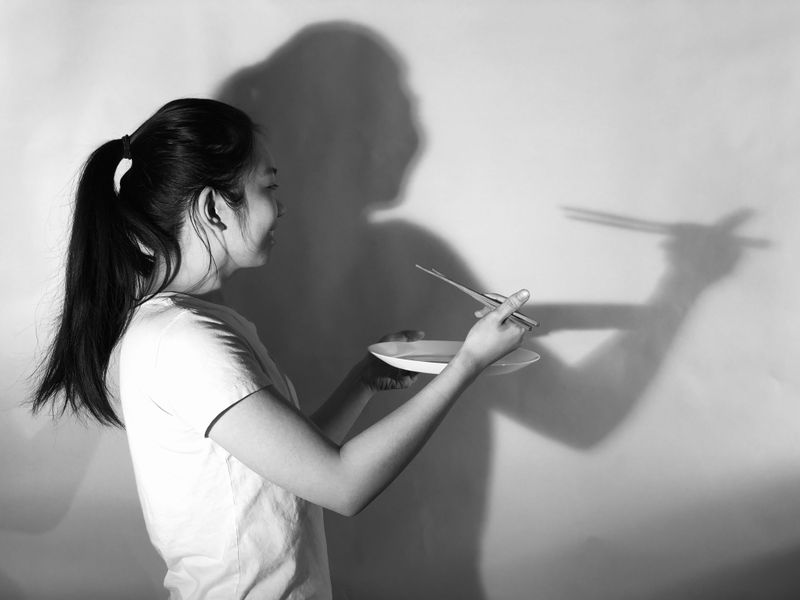

Fried Rice & Family

By Amy

Lowell High School, Lowell, Massachusetts

On a melting summer day when I was 15 years old, I was playing on my phone when I was called to the kitchen by my dad. The reason? I had pestered him for months about how I wanted him to teach me to cook. Cooking is an essential skill for survival. I didn’t want to live by ordering out food all the time. Plus, I wanted to explore cultural cuisines all over the world, starting with the food from my parent’s home country of Vietnam and our ancestors from China.

Before, when I would ask, my dad would either answer with “I’m busy cooking” or “go do your homework.” But some days, while in the kitchen, he taught me basic skills: washing chicken, stirring a soup, chopping meat and flipping the food inside the pan.

As a small kid, I had a lot of failed attempts at flipping eggs that landed on the stove. But I never got in trouble when the egg landed on the stove or on the floor. I wanted to be as good as them. But I never knew how to make a full course family or gourmet dinner.

As a little girl I grew up watching my parents cook. My dad is a retiree and makes great Chinese food, especially Dim Sum. Before travelling to the United States, he was a restaurant manager in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam although our family uses its old name, Saigon. My mom works at an assembly company and makes great Vietnamese food like Phở and Bún bò Huế. Growing up, depending on the dish my parents made, I would rush to their side to see what it was. There were some smells I didn’t like because it covered the whole house with strong scents, for example, salmon. I love to eat fish but the smell disgusted me. I once asked them to make a flambé and my mom did at my request, which satisfied me very much.

But until the age of 15, I was only experienced with making scrambled eggs with rice. I wanted to be like my mom and dad, who cooked passionately and knowledgeably. My dad also wanted me to learn how to cook more of our cultural food because when I grew older he still wanted both my sister and I to care for him to keep our culture alive. He would argue with me about not practicing to speak Vietnamese fluently, as I only knew simple phrases like greetings.

That afternoon in the kitchen, I was excited to have him teach. He instructed me to find the ingredients. I eyed the fridge shelves, but to no avail. He found them, looked me dead in the eyes, pointing at each. I prepared the kitchen for my lesson. He talked me through the order of the ingredients. I grabbed a bowl of rice, eggs, hoisin sauce, chicken powder, black pepper and green onions. I buttered the skillet and followed his directions. He watched me work while sitting at the kitchen table. While I fried the rice, I asked him to tell me a few stories of growing up in Vietnam. He opened up about living in poverty with a huge family of eleven siblings. These were stories he hadn’t really spoken about before. Learning these stories made me sympathize with my father and understand him in a new way.

After we cooked together, I sat down and ate a spoonful of steaming fried rice. It tasted savory and rewarding. I felt proud, carrying the culture from the heart of cooking. When he gave it a try he complimented my cooking as being better than his. Cooking and eating with my dad made me connect with him in a new way.

Having cooked one dish together, I wanted to explore and learn more about not just from my heritage but from cultures around the world for family and friends to enjoy.

© Amy. All rights reserved. If you are interested in quoting this story, contact the national team and we can put you in touch with the author’s teacher.